Vroom: The Virtual Room

The VROOM or Virtual Room was a concept developed at Swinburne, and brought to fruition by the collect

efforts Vroom Inc, incorporating: Swinburne University, Melbourne Museum, RMIT University, Melbourne University, Monash University and

Adacel Technologies Ltd. The Virtual Room opened to the public of Victoria at Melbourne Museum in December 2003.

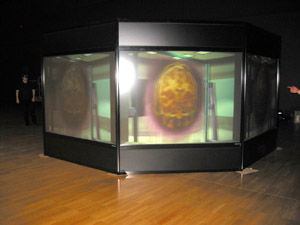

The following describes a unique system for the presentation of virtual objects and worlds. The installation consists of

N walls (N = 8 will be used in this discussion) each of which contains a window displaying stereoscopic 3D images. The walls are

arranged in a circular fashion (octagon) to form a vessel that is supposed to be containing or generating the objects that make up the

virtual environment, see figure 1. The audience walks around wearing passive polaroid glasses (for the stereoscopic effect) and they

perceive virtual objects that appear to be within the confines of the containment vessel.

Figure 1 |

Figure 2 |

Design Concept

The key concept is to create the illusion that the virtual environment is being created by a physical device, the VROOM.

No attempt need be made to present the virtual objects realistically, although for some content that might be desirable. The attempt

is to blur the line between what is physical (the exterior of the VROOM) and the virtual (what is being projected in stereo3D such

that it appears on the interior of the VROOM).

An important implication is that the viewer sees the interior structure of the VROOM, enforcing the sense of virtual

objects within some physical structure, see figure 2. Of course the interior need not appear the same for different pieces of content.

For example, astronomical content might render the interior with a futuristic style while for content based upon artificial life the

interior of the VROOM might take the appearance of a cage or laboratory. The details of how the VROOM is supposed to be creating the

virtual objects might be explained differently as well, perhaps as part of a story being told through the audio system. For some

content the VROOM might be explained as a holographic projector or perhaps a particle transporter, while for other content the VROOM

might be something more down to earth such as a cave or the interior of some ancient architecture.

Another consequence (that should be encouraged) is that when some interesting part of the virtual environment is closer

to, or clearer from, a particular window then any member of the audience can walk around the VROOM to get a better view. For example

in figure 3 while Mars is central, one of the moons might be closer to another window. To get a better view of a particular moon or

even the daylight side of Mars, the audience would go to the relevant window. Imagine a virtual model of a city, in order to look

along a particular street or to look more closely at a particular building one would move around to the best or closest window. There

are very elegant effects that might be achieved using the stereo audio channels at each window. If a dinosaur made a noise near one

window it would be loudest there and less loud (more distant) at other windows. The audio could be another cue that would encourage

the audience to walk around and explore where the sound came from.

Figure 3 |

Figure 5 |

Interactivity

A particular piece of content may or may not require user interaction but if there is then all windows must reflect the

same state. In all cases the illusion of the VROOM is best maintained by all windows showing the correct views of the same

environment. For example, if the VROOM contained an evolving galaxy then it might be interesting enough to watch as just a time

varying system with a audio track. On the other hand, for other simulations the audience might be able to vary parameters using an

input device provided at each window. With a 3D input device, like a wand, members of the audience might be able to project a pointer

into the environment. Imagine an exploratory environment (eg: deep sea) where viewers point with a 3D wand which becomes a beam of

light into the virtual world.

Head tracking would enhance the illusion because then the viewer could look through the windows askew and they would

would be presented the correct stereo pairs as if they were looking through a window on an angle. Like most head tracking systems this

introduces extra complexity, precludes precomputed content, and restricts each window to one viewer at a time.

Concept Images

VROOM top |

VROOM front |

VROOM Panoramics

Virtual Asteroid Display

|

Egyptian tomb. Created by Evan Hallein.

|

Pyramid. Created by Evan Hallein.

|

Jellyfish. Created by Evan Hallein, Natasha Roberg, Alex Harkness. |

Installation (Melbourne Museum, 2003)

|

|