|

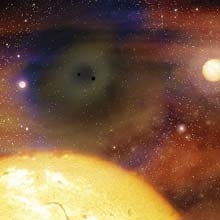

|  | | Artist’s

impression of two black holes evacuating the center of a galaxy.

Credit: Gabriel Perez Diaz; MultiMedia Service; Instituto de

Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC). | |

Using

images from the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have concluded that

two of the most common types of galaxies in the universe are in reality

different versions of the same thing. In spite of their

similar-sounding names, astronomers had long considered “dwarf

elliptical” and “giant elliptical” galaxies to be distinct objects. The

new findings, which appear in this month’s edition of The Astronomical

Journal, fundamentally alter astronomers’ understanding of these

important components of the universe.

Galaxies, the building blocks of the visible universe, are enormous

systems of stars bound together by gravity and scattered throughout

space. There are several different types, or shapes. For example, the

Milky Way galaxy, in which the Earth resides, is a “spiral” galaxy, so

named because its disk-like shape has an embedded spiral arm pattern.

Other galaxies are known as “irregular” galaxies because they do not

have distinct shapes. But together, dwarf and giant elliptical galaxies

are the most common.

For the past two decades, astronomers have considered giant

elliptical galaxies, which contain hundreds of billions of stars, and

dwarf elliptical galaxies, which typically contain less than one

billion stars, as completely separate systems. In many ways it was a

natural distinction: not only do giant elliptical galaxies contain more

stars, but the stars are more closely packed toward the centers of such

galaxies. In other words, the overall distribution of stars appeared to

be fundamentally different.

Alister Graham and Rafael Guzmán from the University of Florida

decided to take a second look at the accepted wisdom. Expanding on work

started by Graham at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC) in

Spain, the pair analyzed images of dwarf elliptical galaxies taken by

the Hubble Space Telescope and combined their results with previously

collected data on over 200 galaxies. The resulting sample revealed

distributions of stars displaying a continuous variety of structures

between the allegedly different dwarf and giant galaxy classes - in

other words, these two types were just relatively extreme versions of

the same object. Moreover, there was one rather interesting caveat.

In recent years, Graham said, a number of studies had revealed that

the innermost centers of giant elliptical galaxies - the inner 1

percent - had been scoured out or emptied of stars. Astronomers suspect

that massive black holes are responsible, gravitationally hurling away

any stars that ventured too near and devouring the stars that came in

really close. This scouring phenomenon had tended to dim the centers of

giant elliptical galaxies, which ran counter to the trend that bigger

galaxies tend to have brighter centers. The dimming phenomenon was one

reason astronomers had concluded dwarf and giant galaxies must be

different types.

Together with Ignacio Trujillo of the Max-Planck Institut für

Astronomie in Germany and Peter Erwin and Andres Asensio Ramos of the

IAC, Graham addresses this phenomenon in a separate article that

appears in the same issue of The Astronomical Journal. Building on

recent revelations showing a strong connection between the mass of the

central black holes and the properties of their host galaxies, Graham

and his colleagues introduced a new mathematical model that

simultaneously describes the distribution of stars in the inner and

outer parts of the galaxy. “It was only after allowing for the

modification of the cores by the black holes that we were able to fully

unify the dwarf and giant galaxy population,” Graham said.

“This helps to simplify the universe slightly because we can

replace two distinct galaxy types with one,” said Graham. “But the

implications go beyond mere astronomical taxonomy. Astronomers had

thought the formation mechanisms for these objects must be different,

but instead there must be a unifying construction process.”

Sidney van den Bergh, former director and researcher emeritus at

the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory at the National Research Council

of Canada in Victoria, said Graham and Guzmán’s result puts to rest a

“very puzzling” question.

“In astronomy, like in physical anthropology, there is a deep

connection between the classification of species and their evolutionary

connections,” van den Bergh said. “The bottom line is that the new work

of Graham and Guzmán has made life a little bit simpler for those of us

who want to understand how galaxies are formed and have evolved.”

|