Our view of the cosmos is veiled by dust and the universe actually shines twice as bright as astronomers had thought, a discovery that will lead to a massive reevaluation of space images.

The Hubble space telescope is perhaps the best known source of the many majestic views of the heavens provided by modern astronomy.

But it turns out that many images will have to be reassessed, after the discovery that a tiny amount of the matter in the universe - about 0.01 per cent of normal matter - causes a haze of dust that obscures our view like a pair cosmic sunglasses.

The implications for understanding how the very first galaxies - huge masses of stars - evolved after the big bang 13.7 billion years ago are "scary", said Dr Simon Driver from the University of St Andrews, one of the international team.

In effect, the find means that people have underestimated the size and brightness of distant galaxies and this realisation will have a profound impact on understanding how they winked into being.

"A lot of conclusions will have to be revised, notably about the evolution of galaxies."

Just as surprising is that many of his peers have mostly ignored the effects of dust.

"For nearly two decades we’ve argued about whether the light that we see from distant galaxies tells the whole story or not. It doesn’t; in fact only half the energy produced by stars actually reaches our telescopes directly, the rest is blocked by dust grains."

While astronomers have known for some time that the universe contains a sprinkling of dust, they had not realised the extent to which this is restricting the amount of light that we can see.

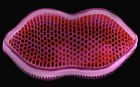

The dust absorbs starlight and re-emits it, making it glow.

They knew that existing models were flawed, because the energy output from glowing dust appeared to be greater than the total energy produced by the stars, suggesting they were missing something important.

To work out the true effects of dust, Dr Driver’s team combined an innovative new model of the dust distribution in galaxies developed by Dr Cristina Popescu of the University of Central Lancashire and Prof Richard Tuffs of the Max Plank Institute for Nuclear Physics, with data from the Millennium Galaxy Catalogue, a state-of-the-art high resolution catalogue of 10,000 galaxies.

"We have new approach, new data and new models and the answer is embarrassing large," said Dr Driver.

The key test that the new model passed was whether the energy of the absorbed starlight equated to that detected from the glowing dust, after it reemits the absorbed energy.

The numbers fitted perfectly, the team reports in the Astrophysical Journal Letters The Universe is currently generating energy, via nuclear fusion in the cores of stars, at a whopping rate of five quadrillion Watts per cubic light year - about 300 times the average energy consumption of the Earth’s population.

Dr Driver continues, "We still aren’t able to observe the Universe in its full glory, however we do now better understand the effect that all of this dust is having on scientific observations."

He said the dust issue is overshadowed by another one: dark matter, that is a kind of matter that is invisible but that can be inferred by its gravitational pull. Telescope observations show that stars account for only about one per cent of the mass of the universe.

Ghostly neutrino particles contribute, at most, a similar amount.

Throw in gas clouds, planets and other objects, and you get another 10 per cent. That leaves about 85 per cent unaccounted for: dark matter.

Thanks for posting. Would you like to edit your profile?